What is Japanese knotweed?

Read on as we explore Japanese knotweed’s scientific background, varieties and origin

Quick facts

- Invasive, non-native species that's difficult to control.

- Growth is visible from early spring to late autumn.

- Can cause damage to hard landscaping and vulnerable structures.

- Professional treatment or removal is always advisable.

“We estimate that approximately 4% of homes in the UK are affected by Japanese knotweed, either directly or indirectly (i.e. neighbouring an affected property), impacting their value by an average of 5%.” Nic Seal, Founder of Environet UK

Japanese knotweed Identification

Japanese knotweed is not always visible throughout the year and to make identification even trickier, the appearance of Japanese knotweed changes depending on the time of year. In early spring, you may see bright red buds growing from the plant’s crown in the ground. From these buds grow thick shoots resembling asparagus quickly growing with bamboo-like canes. You may also see small radial plants appear that are normally deep purple or red which quickly turn green producing shield-shaped leaves.

By summer, mature plants grow to 2-2.5 metres, with lime-green leaves forming alternately on the stems, and clusters of creamy-white flowers. In autumn, the leaves turn yellow before falling off and the stems become brittle and brown. In winter look for brown, brittle canes, distinctive crowns, and zigzag stem distribution. Expert guidance ensures correct identification year-round. For more information, please read our Japanese knotweed identification guide.

Japanese knotweed removal

When it comes to removing Japanese knotweed, it’s always best to leave it to the professionals.

DIY removal is usually ineffective, leading to root regrowth or even a bigger infestation. Removal involves meticulous processes, ranging from herbicide treatment to full excavation.

At Environet, we’ve spent the last 27 years refining these methods and providing fully tailored approaches to our clients. We start with a free identification service, followed by a thorough survey to decide on the best approach to fully remove all the plant, leaving properties knotweed-free.

If mechanical removal is needed, our innovative, trademarked excavation methods like DART™ and Resi-Dig-Out™ will be employed, with the latter being herbicide-free, cost-effective, and eco-friendly.

For ultimate peace of mind, we provide insurance-backed guarantees for up to 10 years, meaning that if there is any regrowth post-treatment, we’ve got you covered!

For more information, please visit our Japanese knotweed removal page.

Quick Links

Introduction to Japanese knotweed

- Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) is a herbaceous, perennial plant that is widely distributed across the UK.

- Growing from crowns similar to rhubarb, it emerges in spring, rapidly growing to its full height of over 2 metres by early summer. This aggressive growth pattern gives it a significant advantage over native plants, making it extremely invasive.

- Creeping rhizomes spread out from the main plant, exploiting gaps and weaknesses in any structure it encounters. These rhizomes easily fragment and quickly establish new plants, making control of the species particularly difficult.

- Specialist removal is always advisable, and often a prerequisite to lending for mortgage purposes.

- There are also several pieces of UK legislation covering the species.

What is the scientific background of Japanese knotweed?

Japanese knotweed has been reclassified several times since it was first named, moving between the Polygonum, Fallopia and Reynoutria genera.

The Polygonaceae are a family of flowering plants known informally as the knotweed family. There are around 1200 species in the family, broken down into 48 genera. The knotweed family contains some of the most prolific weeds, including species of Persicaria, Rumex and Polygonum.

Species in the genus Reynoutria are characteristically robust erect perennials that grow from rhizomes. The boundaries of Reynoutria have been much confused; and as a result it has been repeatedly merged with and separated from Fallopia. This is why Japanese knotweed is still commonly referred to as Fallopia japonica.

In its native range Japanese knotweed spreads both by seed and vegetatively, but in the UK the plants are all female. This means that although seeds are often produced, they are infertile and cannot produce new plants. All plants in the UK are therefore a result of growth from root and stem fragments.

The rapid spread of Japanese knotweed across the UK is largely attributed to its amazing ability to reproduce vegetatively from very small fragments of rhizome.

Originally bought and sold across the UK as a prized garden ornamental, it now largely spreads via natural expansion of existing stands and uncontrolled movement of infested soil.

In the UK, the species is most widely known as Japanese knotweed although it is also referred to as Asian knotweed, Pea shooters, and Donkey rhubarb. In Japan, where the plant is thought to have originated over 125 million years ago, it is known as Itadori.

What varieties of knotweed are there?

Fallopia x Bohemica syn. Reynoutria x Bohemica

Bohemian knotweed

Bohemian knotweed (Fallopia Bohemica syn. Reynoutria x bohemica) is a rare hybrid of the highly invasive Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) and its larger cousin Giant knotweed (Fallopia sachalinensis). Unlike its parent plants, it can produce fertile seeds, enabling it to spread more rapidly.

Bohemian knotweed arose not long after the arrival of Giant knotweed in the UK in the late 1800s, although its presence was not reported in the wild until 1954, in County Durham.

Spread of the plant by seed is relatively uncommon, with the main distribution of plants attributed to vegetative spread via the rhizome system as with Japanese knotweed.

As well as outcompeting native species, its vast root system has the potential to cause damage to property, including patios and driveways, which is seldom covered by buildings insurance, meaning the plant should be treated or removed as quickly as possible.

The economic impact of this species is similar to that of Japanese knotweed in that it’s a problem for developers of infested land, although it is not entirely clear whether with Bohemian knotweed is actually covered by the letter of the law that proscribes Japanese knotweed when it comes to property transactions.

Key characteristics

- Green leaves either heart shaped, or square ended. Both types can appear on the same plant.

- Larger than Japanese knotweed, but smaller than Giant knotweed, and have short hairs on the underside.

- Plants usually grow 2 – 3 metres high.

- Small green-white, or cream-white flowers that grow in plumed clusters.

- Cane-like stems are reddish-brown in colour. The plant dies back above ground in the autumn, but the canes usually remain standing.

Fallopia Sachalinensis

Giant knotweed

Giant knotweed (Fallopia sachalinensis) was introduced to the UK in the late 1860s, appearing in the 1869-70 catalogue of William Bull of Chelsea. Like Japanese knotweed, Giant knotweed seems to be very tolerant of a wide range of soils from volcanic ash to muddy riverbanks, although its vast size makes it vulnerable to drought. Its huge proportions meant it was not as popular with gardeners as its smaller cousin, which could account for it being less common both in the wild and within residential properties.

Although closely related to Japanese knotweed, Giant knotweed is easy to differentiate as it is a much larger plant, 4-5 m tall with much larger leaves 20-40 cm long. Another key difference is the shape at the base of the leaf which in F. sachalinensis is rounded, forming a heart shape.

Giant knotweed appears on Schedule 9, Part II of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981.

Key Characteristics

- Green heart-shaped leaves can grow up to 40 cm long and up to 27cm wide, fine white hairs, known as trichomes, can be found on the undersides.

- Flowers in late summer or early autumn, green-white in colour forming dense clusters.

- Plants typically reach 3-4m in height but can be as much as 5m.

- Typically green canes.

Reynoutria Japonica var. Compacta

Dwarf knotweed

Dwarf knotweed is an uncommon variety of Japanese knotweed that is rarely found outside of ornamental gardens. This petite variety rarely reaches over 1m in height, and has smaller leaves, generally up to 11cm long and 10cm wide. It retains the distinctive ‘zig zag’ stem structure, but the leaves are darker green with crinkled edges and reddish veins. Upright clusters of white or pale pink flowers appear in late summer.

Compacta is not as aggressive as R. japonica, but it does have the ability to reproduce sexually and therefore has the capacity to spread more easily. It can also hybridise with Giant knotweed.

Again, although it shares its classification with R. japonica, it is not entirely clear whether with compacta is covered by the letter of the law that proscribes Japanese knotweed when it comes to property transactions.

Key Characteristics

- Small (8-11cm), dark green leathery leaves with red/purple veins and stems, turning red in autumn.

- Flowers in late summer – white/pink flowers turning dark pink/red in late autumn.

- Plants typically reach 0.5 – 1m in height.

Persicaria Wallichii / Koenigia polystachya

Himalayan knotweed

Himalayan knotweed is a large, thicket-forming plant, reaching up to 2m tall, and has become established in river systems, hedge banks, on woodland edges, roadsides, railway banks and waste ground. It is especially common in South West England.

It is not currently covered by any legislation in the UK, but its invasive nature should not be underestimated. It grows vigorously, creating large, dense stands that exclude native vegetation and prevent tree saplings from establishing.

Although a similar size to Japanese knotweed, the similarities in appearance end there. Himalayan knotweed grows from much smaller, green stems, with large tongue or lance-shaped leaves. Flowers are white clusters with pink centres. Brown, fertile seeds form in autumn. Seeds of the plant are dispersed by wind and water, while rhizome and stem fragments are dispersed in waterways, by flooding and through mechanical ground disturbance.

Key Characteristics

- Long tongue / lance shaped leaves, 9-22cm long × 3-8 cm wide, sometimes fine hairs on underside.

- Flowers in late summer – long clusters of creamy white or pale-pink flowers.

- Plants typically reach 40 – 180cm in height.

- Smooth, green, branching, upright stems.

Where did knotweed come from?

Japanese knotweed is a pioneer species that is believed to have its origins in the volcanic mountains of Japan some 150 million years ago. Its ability to survive in hostile conditions at high altitude, helped it to gradually spread across what is recognised as its native territory of Japan, Korea, Taiwan and parts of China.

Across Japan it is known as Itadori, and is foraged for food and used in traditional medicines. Japanese knotweed is known to contain resveratrol, a chemical also found in red grapes, which is thought to act like antioxidants do, protecting the body against damage that can put you at higher risk of things like cancer and heart disease.

Crossing continents

During the Victorian era, European pioneers travelled the world collecting exotic plant and animal specimens to bring home and sell – In effect founding the horticultural market as we now know it. It was one such pioneer, a Bavarian physician and keen botanist Philipp Franz Von Siebold who came across Japanese knotweed. Siebold collected thousands of plants during his posting in Japan in the Dutch trading post on Deshima, including many of our garden favourites such as the peony-rose, hydrangea, camellia and wisteria.

Siebold returned to Holland with his collection and founded a commercial nursery in 1840. From there, samples of his plants were distributed and sold across Europe. Japanese knotweed was sent to Kew Gardens in London in 1850, and with a gold medal awarded by the Agricultural and Horticultural Society in Utrecht to its name, it became a firm favourite amongst nurserymen and gardeners alike.

There are also reports that an earlier sample was sent to the Royal Horticultural Society in London in 1825 – although it is not believed to have been widely distributed at that time.

Japanese knotweed has now spread across the continents and is a problem in several countries including North America, Canada and New Zealand.

A look at the UK

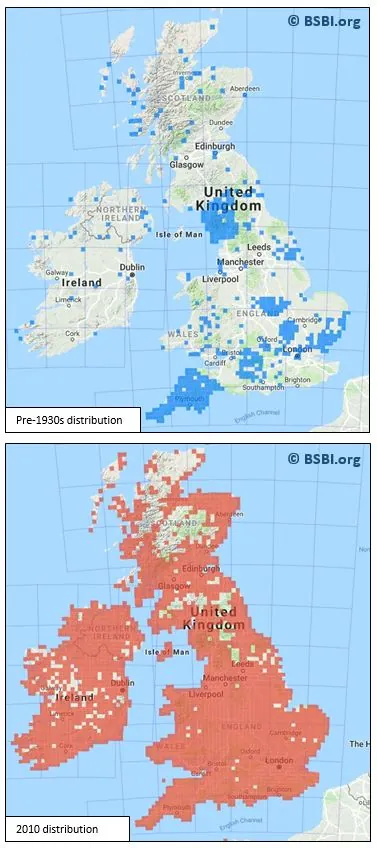

By 1869 Japanese knotweed was widely available for sale to the public in the UK and was even used by farmers as animal feed. It was also noted for its industrial applications such as the stabilisation of railway embankments and spoil from mines.

As we know, fashions come and fashions go, and by the time the fashion went there was no stopping the invasive species spreading throughout the UK. The rapid industrialisation and development of infrastructure across the country, coupled with the lack of biosecurity allowed knotweed to spread exponentially.

By 1900 it had been reported as naturalised across the UK, where it was found growing outside of gardens in many parts of the country. As early as the 1930s, it started to negatively affect the price of housing, and was known locally in Cornwall as “Hancock’s curse”.

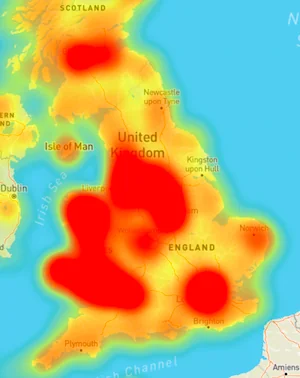

We now estimate that up to 1 in 20 residential properties are affected in some way by Japanese knotweed, with a presence in every 10 square km patch of the UK.

Why is knotweed so problematic?

Environmental

From a biodiversity point of view, Japanese knotweed is an aggressive and invasive species that quickly outcompetes our native flora. Evolved to tolerate much harsher conditions, our temperate climate, fertile soils and a lack of natural predators mean knotweed has the advantage. For that reason, Japanese knotweed was listed on Schedule 9 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, making it an offence to plant or otherwise allow it to grow in the wild.

Damage

The aggressive nature of the plants, and ability to survive in unfavourable conditions mean that they can cause damage to the built environment too. We often see cases of damage to hard surfaces such as patios, asphalt and drains. Although it is a myth that knotweed can grow through solid concrete, it certainly has no problem exploiting the smallest of gaps and weaknesses, eventually causing real damage. For further information on the type of damage knotweed can cause, check out our short video or read more.

Legal implications

Given the damage that knotweed can potentially cause to property, banks and building societies in the UK have imposed strict lending criteria where knotweed is identified. The Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors published guidelines for their members on reporting and assessing the risk from infestations in 2012. As a result of this, the Law Society added a question about knotweed to the pre-enquiry form (TA6) used in the sale of property, meaning vendors now have an obligation to declare knotweed on their property.

It is widely acknowledged that the presence of Japanese knotweed on a property can negatively impact its value and saleability. Thankfully, many lenders take a pragmatic approach and with the right treatment programme and guarantee in place, you should have no problem selling a property affected by knotweed. At Environet we have successfully helped hundreds of people through the sale process. Read more about selling an affected property here.

“Those who discover the plant on their land should seek professional advice and put a treatment plan in place as quickly as possible, to preserve the value of their property and to protect themselves from the risk of litigation if the plant is allowed to spread.”

Emily Grant, Director of Operations.

What can be done about it?

Removal

Removal of Japanese knotweed gives the most certainty that the plant has gone for good, leaving little to no restriction on the use of the area after the works have been completed. Although the initial cost is usually higher, more and more people are opting for certainty that the problem has been completely removed. Removal may involve complete excavation and disposal of the affected soil, or the more eco-friendly and cost effective in situ process of soil screening we call Xtract™ / Resi-Dig-Out™.

Treatment

Where knotweed causes minimal restriction to amenity value, and can be left undisturbed, control through herbicide treatment over 3-5 years may be an acceptable option. Delivered via a foliar spray, or through stem injection, chemicals are used to slowly weaken the rhizome system, eventually supressing new growth.

“Despite the challenges, eradication of knotweed should always be the goal and most homeowners and buyers will want reassurances that the problem has been dealt with and knotweed isn’t going to rear its head at some point in the future.”

Mathew Day, Finance & Technical Director

Eating it

Did you know that the tender young shoots of Japanese knotweed are actually edible? That’s right, despite its fearsome reputation, it’s a highly prized treat in the wild foraging community! Packed with vitamins, with a lemony rhubarb flavour it can be used in both sweet and savoury dishes. Although eating knotweed is arguably good for you, it’s not going to solve your knotweed problems. Furthermore, we’d advise against it unless you can be sure that the plants have not been treated with chemicals in the past and are growing in uncontaminated ground.

Image credit: Marie Viljoen

Start fixing your invasive plant problem today by requesting a survey

Request a survey

Rest assured, where invasive species are identified at an early stage and tackled correctly, problems can usually be avoided. Our specialist consultants complete thorough surveys to identify the extent of the problem. Our plans aren’t one-size-fits-all; they’re customised to tackle the invasive species at your property effectively, taking account of all of your requirements.

GET IN TOUCH

Contact us

Our team of experts is available between 9am and 5:30pm, Monday to Friday to answer your enquiries and advise you on the next steps

Want a survey?

Request a survey online in less than two minutes by simply uploading a photograph and providing a few brief details. A member of the team will swiftly come back to you with further information and our availability.

Need quick plant identification?

Simply upload a few images of your problem plant to our identification form and one of our invasive plant experts will take a look and let you know, free of charge what you are dealing with. We’ll also be there to help with next steps where necessary.